SCRIPT TEASE: Interview with Mike Lynch

A full time cartoonist with roots in vaudeville!

For my final Script Tease of 2025 I am thrilled to present my interview with cartoonist Mike Lynch!

EERIE: Hi Mike! Before we begin, would you please describe yourself and your work?

MIKE: I draw cartoons and illustrations for a lot of clients (Mad magazine, Reader’s Digest, Wall Street Journal, McGraw Hill, Random House, etc.). I’m also an adjunct professor and I teach the history of comics and the history of political cartoons and the history of illustration. I also give talks about the medium. I am a full-time freelancer, which means that I draw for a living. No day job.

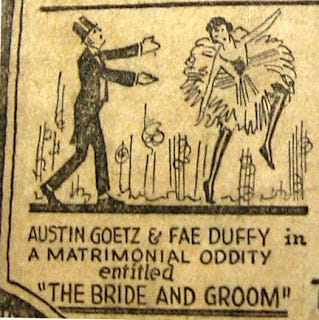

EERIE: When we spoke earlier, you let me in on a fantastic detail, your family’s history goes right back to the vaudeville stage! Vaudeville is known for exaggeration and absurdity. Do you think that kind of humor has influenced your cartooning?

MIKE: Yes, my great grandparents were a professional Vaudeville act for 30 years. My own parents first met while working at the Kalamazoo Playhouse. Later on, my Dad went back to college, obtaining a Ph.D., and my Mom sold real estate. As for me, I alway liked performing and drawing. I remember being in the big year-end 8th grade talent show, and when word got around to my great grandmother, she exclaimed, “It’s wonderful to see someone in the family finally return to the theatre!” When I was in high school and college I made money being part of a professional improv company of players. Great fun! But I realized that it took a lot of time to deal with a group. Telling stories by drawing is easier to manage. I have always liked cartooning since I was a little kid and my Dad gave me a copy of Bill Mauldin’s The Brass Ring and Gordon Parks’ A Choice of Weapons. Two great books about creativity and the choices people make. More importantly, he gave me copies of his old Pogo books by Walt Kelly -- one of the most absurd and beautiful newspaper comic strips. So, yeah, you’re right. I like absurd. I like writing that turns people’s expectations on their heads.

EERIE: In my burlesque acts I rely on a formula of setup & reveal. So far, I’ve been comparing this to the formula of a multi-panel cartoon strip.

Do you think this also applies to single panel cartoons?

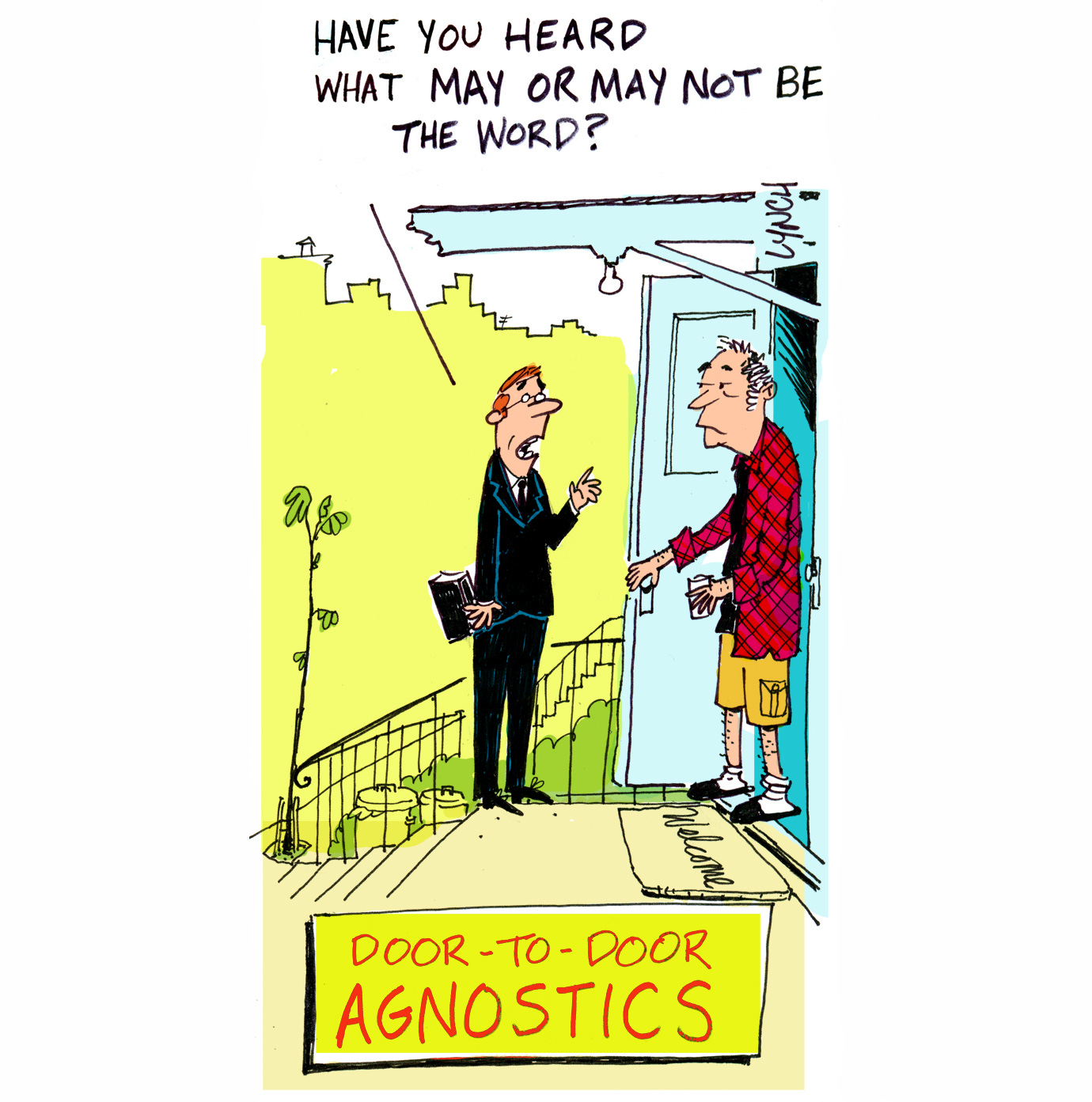

MIKE: Yes. A successful single panel gag cartoon has to work in 3-5 seconds. And there has to be a story, even in that one panel. I mean, here’s a for instance: when there’s a salesman-looking guy at the door asking the homeowner, “Have you heard what may or may not be the word?” -- that’s the set up. The reveal is then in the second thing you read, in the legend below, “Door-to-door Agnostics.” This disrupts the expectation that a salesman has a definite hardcore pitch. And it’s absurd that the concept of doubt would need to be proselytized. Maybe it should! So, a cartoonist takes an expectation and turns it on its head.

EERIE: In both our worlds, the audience needs to “get it” instantly. What techniques do you use to make the joke land in one glance?

MIKE: Yeah. This is a juicy question with a deeply personal answer. How do you make sure that you and your audience are on the wavelength? Well, you can’t. All you can do is shoot your bolt. I mean, you show up, do the work and, like it or not, it’s the audience that decides if it “works.” And if it doesn’t work, you can’t blame them. You just have to keep trying. Creative people are not born successful. One thing that The New Yorker cartoonist George Booth told me was that he faced constant rejection when he first showed his cartoons to The New Yorker. It was only when he began drawing cartoons that made HIM laugh -- cartoons that were idiosyncratic and odd and definitely “Boothian,” that that was when he began to sell frequently to them. It starts with your own sensibilities. And then you persist and you get better. It was the kinetic artist, George Rhoads, who told me, You’ll never be any good unless you do this full-time. He’s right, and he inspired me to leave my regular job.

EERIE: In burlesque I often use silence and stillness as a technique for more impact. Have you found a cartooning equivalent? A place where minimalism is funnier than adding more detail?

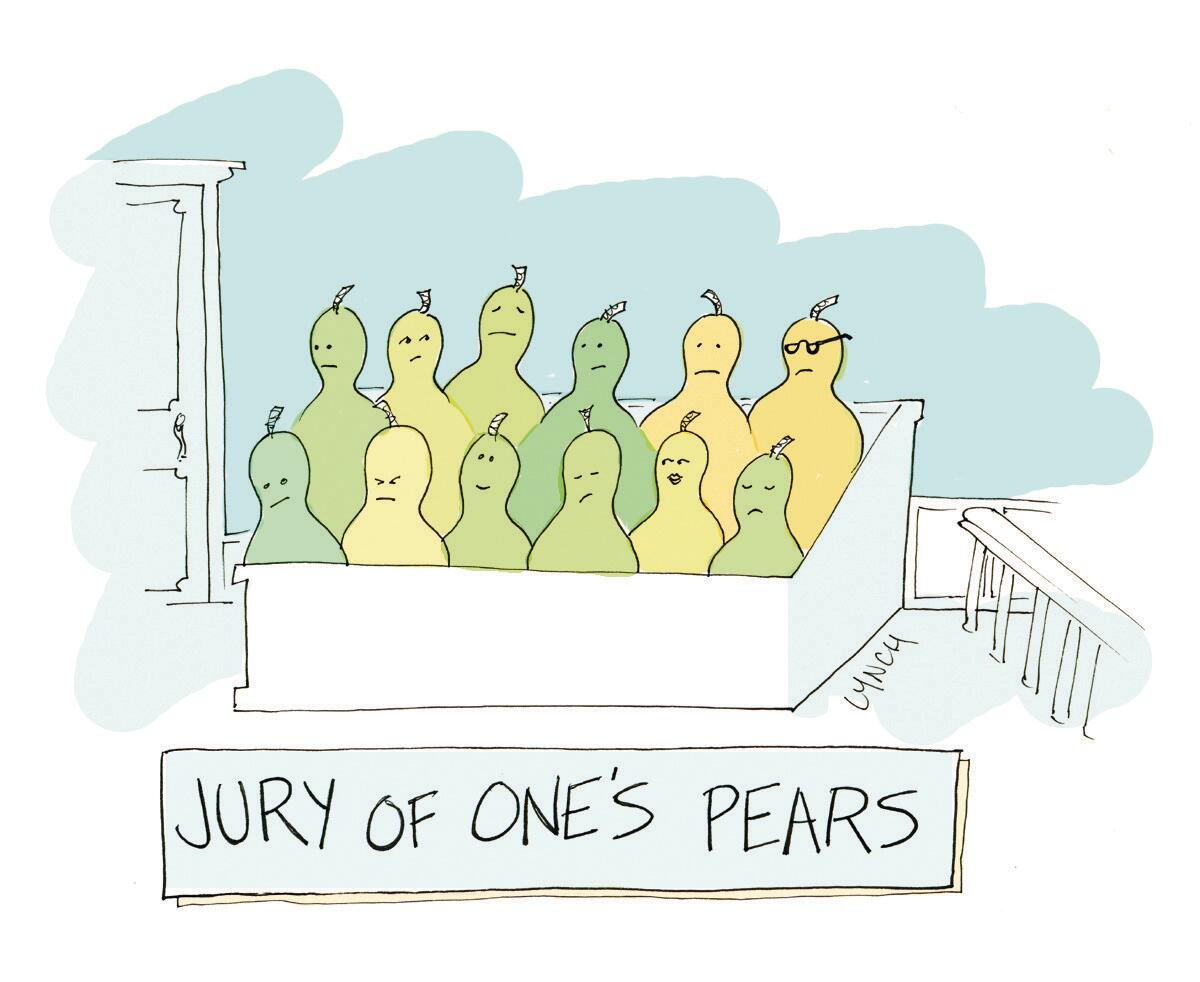

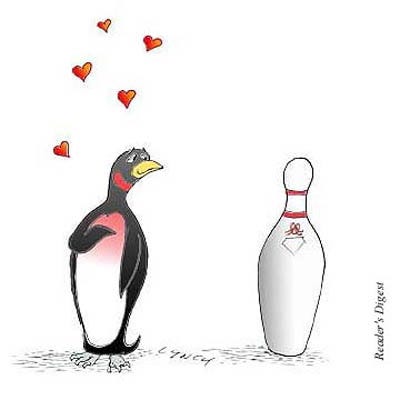

MIKE: I guess the equivalent with a gag cartoon would be wordless cartoon. Cartoons that depend only on the visual are the purest form of humor. And they are the hardest to write. I drew a cartoon of a penguin in love that was much-reprinted. No words. The reader has to put it together. You have to really trust to be able to do that. The drawing is always secondary to the idea.

EERIE: How much has the cartoonist career changed since you first started? What’s harder now? And what’s easier now?

MIKE: I think things have changed a lot. For me, old markets are gone, but people still love cartoons. That won’t change. Last month, I sold some cartoons to Reader’s Digest, sold some more to another magazine, sold some cartoons at Cartoonstock.com, taught some classes and gave a couple of lectures to the National Education Administration about comics. This was all part of my income stream. I also made time this year to attend the National Cartoonists Society annual Reubens weekend and met a lot of people. It’s always great to talk shop and get new ideas. As long as you keep moving forward -- and for me, that’s teaching and pitching new cartoon ideas. Rejection is normal and you can’t take it personally. And you can’t stop. That hasn’t changed.

EERIE: What advice would you give to someone who wants to start cartooning?

MIKE: My advice is to talk yourself out of it. I don’t mean to be mean, but it’s not for everyone. I know my parents were generally supportive, as were my friends, but no one had any clue how this all worked; how you draw something on your board and then how the thing gets published and you get money. If, however, you feel that this is a calling and you will be a horrible, miserable human being if you don’t do it (which is what happened to me), then, by God, you are stuck! But there is no clear path forward, as you know. Work on stuff that you want to do, but also look at what’s selling. I believe what we do (creative people who want to be professionals) are in the commercial arts and by that I mean creating work that makes money. I also know that when and if you get a meeting with an editor, for instance, they will likely ask why the project you’re pitching will be successful. Be ready to be a salesperson. It’s not fair to ask a creative person this, I think. Not at all. But that’s the reality.

I really enjoyed talking with Mike Lynch!

Here’s a link to his blog where you can follow for more.

https://mikelynchcartoons.blogspot.com/